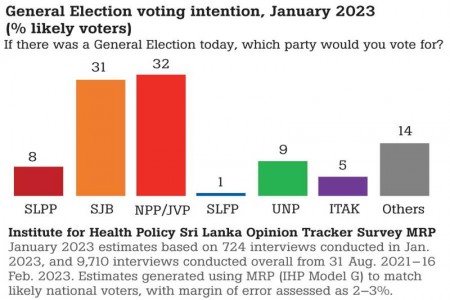

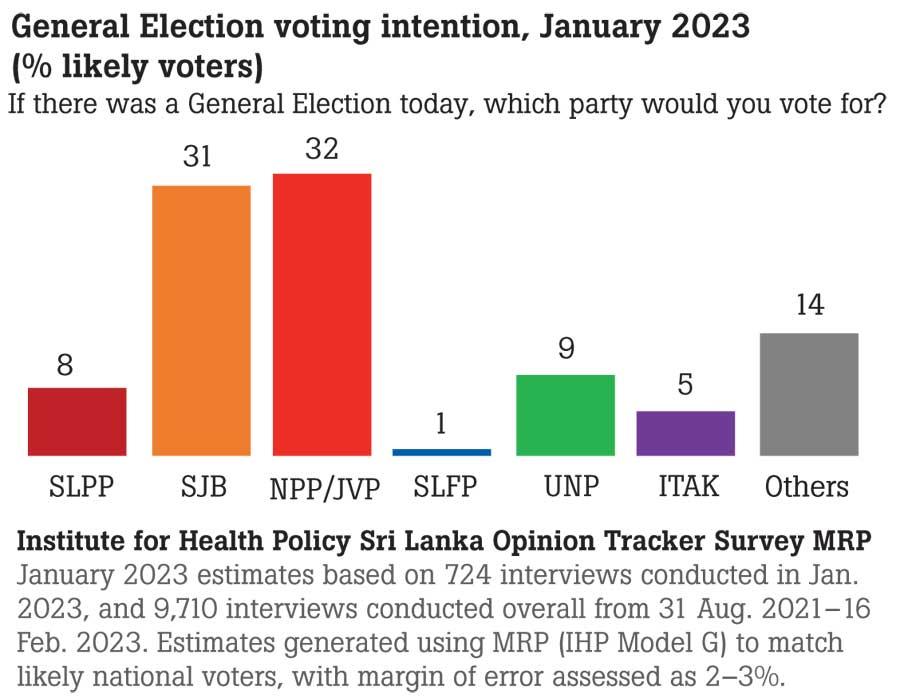

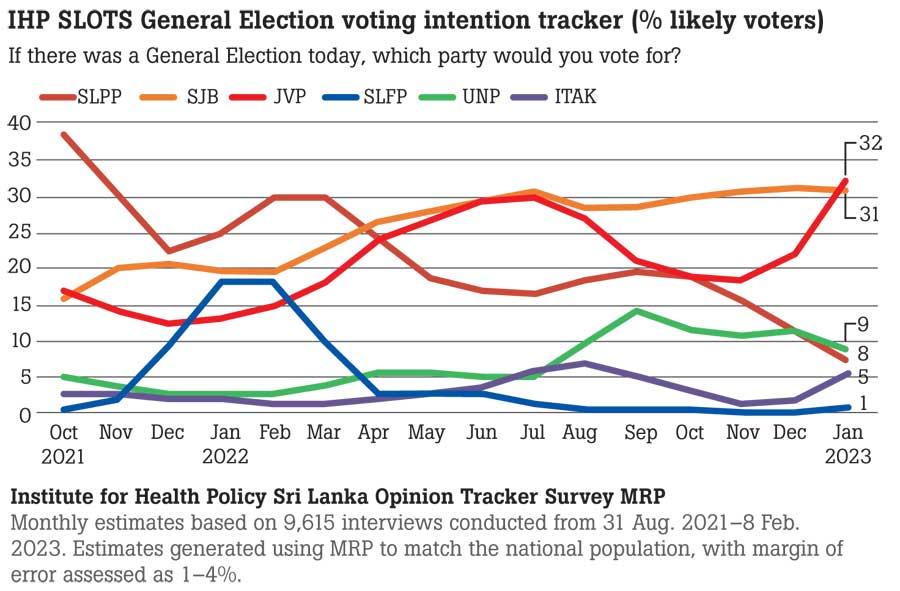

IHP MRP analysis of likely voters indicates that since July 2022, when President Ranil Wickremesinghe took office, the SJB has gained three points, the NPP/JVP one point, and the UNP five points. This has largely been at the expense of the SLPP whose support fell 11 points.

Assuming general election voting intent transfers to voting in local authority elections due in March, our January polling suggests that the SJB and the NPP/JVP between them will win the plurality in most local authorities and wards.

However, most local authorities are likely to end up with divided control, with no party winning an absolute majority. The SJB and ITAK will lead the NPP/JVP in the Northern and Eastern provinces, but the NPP/JVP is likely to lead the SJB in the Western, Southern, North-Central, and Sabaragamuwa Provinces, and will do better in rural areas, whilst the SJB will do better in urban and municipal councils.

Assuming the local authority elections in March reflect these general election vote preferences, they will represent a huge change from the previous 2018 results, which were dominated by the SLPP. Five factors are driving this change.

First, less than one in seven 2020 SLPP voters intend to vote for the party, with this being less than one in ten of Tamil and Muslim SLPP voters.

Second, defecting SLPP voters prefer the NPP/JVP (35%) more than the SJB (19%). These are primarily Sinhala voters, with Tamil and Muslim ex-SLPP voters preferring the SJB to the NPP/JVP.

However, most local authorities are likely to end up with divided control, with no party winning an absolute majority. The SJB and ITAK will lead the NPP/JVP in the Northern and Eastern provinces, but the NPP/JVP is likely to lead the SJB in the Western, Southern, North-Central, and Sabaragamuwa Provinces, and will do better in rural areas

Third, 2020 SLPP voters are 10–15% more likely than other voters to say they will not vote, further depressing the likely SLPP vote. NPP/JVP voters are also less likely to vote than SJB voters, reducing its margin in likely voters by 2%.

Fifth, the NPP/JVP is doing better than other parties in holding onto its 2020 supporters, with 56% of its previous voters preferring the NPP/JVP compared with SJB which retains the loyalty of just 36% of its 2020 voters. The UNP has done even worse, retaining only one in ten of its 2020 voters, but this has been more than compensated by defecting 2020 SLPP voters, who contribute the largest share of its current support base.

A consequence of these movements is that the current support base of all the major opposition parties except the SJB and ITAK is dominated by former SLPP voters. It suggests that most of these voters have not yet found a permanent home. The fluctuations in support for the NPP/JVP in recent months, which first peaked in July before falling, and then again surging in the past three months would suggest that the support of these voters remains fickle and very much in play.

Nevertheless, the electorate remains highly divided with no party or two parties emerging as the clear choice of the public. This suggests that the electorate remains unsure who to vote for and correspondingly that no political party has succeeded in capturing the imagination of the long-suffering Sri Lankan people.

How IHP generates its voting intention estimates

IHP estimates voting intentions using data from the Sri Lanka Opinion Tracker Survey (SLOTS), which is a joint initiative of IHP and researchers at several local universities. SLOTS is a national phone survey that has been tracking public opinion every day since August 2021, conducting about ten thousand interviews since it started. SLOTS asks respondents who they voted for in the 2019 and 2020 elections, and who they intend to vote for in a future presidential and general election. Respondents are drawn from a mixed sample of a national representative panel of respondents previously recruited in 2019 through face-to-face interviews from all parts of the country, and others reached by randomly dialing mobile numbers.

To manage the challenges posed by small monthly interview samples (N= 400–1,000) and a substantial level of refusals to answer questions about voting, IHP uses a form of Multilevel Regression and Post-Stratification (MRP) to estimate voting intention in each month. MRP is an approach that is increasingly used by pollsters in other countries to leverage small and biased samples to track voting intention. Its most notable use was by YouGov in predicting the Brexit referendum and the 2017 and 2019 elections in the United Kingdom, where MRP performed more robustly than traditional

polling methods.

IHP’s MRP approach involves first modelling past voting choices in respondents who disclosed this and then multiply imputing the past vote choices of all respondents in the full survey. These are then weighted to match the national population along multiple dimensions, including age, sex, ethnicity, religion, education, socioeconomic status, geographical location, sector, and the 2019 and 2020 election results. In the second step, the data from interviews in any given month are modelled across the full sample of almost 10,000 respondents to estimate current voting intention in the national electorate, and the final estimates are adjusted for the likelihood of voting which uses data from a question asking if people will vote.

IHP’s estimates come with some uncertainty as it uses sample data and makes various assumptions during analysis. Additionally, some respondents who currently say they will vote for other parties may vote on the day for one of the major parties making our predictions under-estimates. Each major party’s share of vote intentions in January 2023 is likely to be associated with a margin of error of 2–3%.

To receive further details and future updates, please contact IHP by email at info `@’ ihp.lk